| Main | Stag beetles' life cycle |

Illustrated stag beetle Lucanus cervus life cycle

Stag beetles have a very secluded long life cycle, spent mostly underground, and this page is an attempt to illustrate it step-by-step; the photos on this page have been taken over the years by several authors and are their copy-write.

Understandably there are still a few gaps to cover, so contributions are always very welcome.

Breeding season: from the end of May until the beginning of August out in the open air. As soon as the beetles emerge all they want to do is to mate.

Stag beetles clinging to ivy in the mating position. Photo by John Allen.

|

Stag beetles mating during the evening under a car. Photo by Maria Fremlin, 7 June 2003.

|

Stag beetles mating during the night. Photo by Maria Fremlin, 17 June 2006.

|

Male stag beetle attempting to mate with a dead female. For another photo click here. Photo by Maria Fremlin, 6 July 2007.

|

It is not that easy to find stag beetles mating, these photos are the result of very lucky encounters!

For more about their mating behaviour in the wild, click here.

Eggs: nobody knows for sure how many; but in captivity a female may lay around 30 eggs, in some cases up to 90 *.

In the field females probably do not lay all their eggs in one “basket”, sometimes they might go from stump to stump. Possibly this is what they are doing when one sees them walking about during the season [1 & 2].

The eggs are laid singly in the soil next to rotting wood. Before a female lays them, she may take a long time carefully preparing her nursery, digging around, chewing pieces of wood, and compacting them near the dead wood.

Afterwards the female compacts the substrate to form a hollow and only then she will lay an egg in it. It is believed that the female does this by telescosping her abdomen, just like she did during post-eclosion, and in the process pass on a “starter pack” from her mycangium. It will contain important micro-organisms essential to aid the larva digest its food; but this has only observed once with one stag beetle species in Japan [3].

Finally, she may cover it up with more substrate, see “egg ball” below.

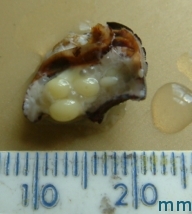

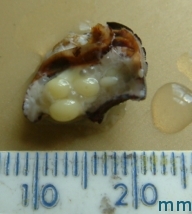

Eggs found inside a female which had been trodden on while on her way to lay them. They are oval shape and surrounded by fat. Photo by Maria Fremlin, 2003.

|

A female stag beetle has laid some eggs in the soil next to a piece of wood where larvae were feeding in captivity. Note the eggs have become spherical. Fertilised eggs take up moisture as the larvae grow inside. Photo by Paul Hendriks, 9 June 2011.

|

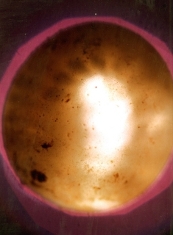

View of an “egg ball” found also in captivity; this time the female was placed in a special mould, no wood.

Photo by Christian Molls.

|

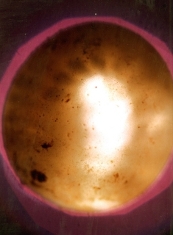

View of a nearly mature egg found inside an “egg ball”. It has now swollen up and almost filled in the hollow. Somehow the female managed to compact the mould in such a way as to leave the perfect space all around the egg. Perfect fit!

Photo by Christian Molls.

|

View of an egg showing the larva developing inside it; it is now 3 by 3.4 mm. In order to come out the larva will cut the shell with its pincers and probably with its egg-bursters as well.

Photo by Dr Eva Sprecher.

|

The eggs take about 3 weeks to hatch.

Return to the top

Larval stage: in the UK it migth take as little as 2 years for a tiny fragile grub to mature [4]; but it will take at least 3 years in the Continent because they are bigger [5]. Note the weight of the larva in the last photo below, 21.5 g. In the UK their maxium weight is about 13 g. Possibly, depending on the circumstances, it might take even longer; this rather is difficult to prove in the field, though.

First instar:

age - two days

weight - 0.02 g

HCW - 2.4 mm

length - 5 mm

Photo by Dr Eva Sprecher.

|

Second instar:

age - twenty two days

weight - unknown

HCW - ~5 mm

length - ~4.5 cm

Photo by Paul Hendriks.

|

Third instar:

age - ~4 months

weight - 3.3 g

HCW - 10 mm

length - unknown

Photo by M. Fremlin.

|

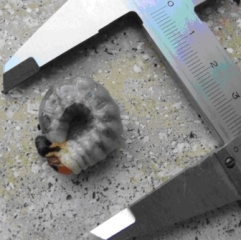

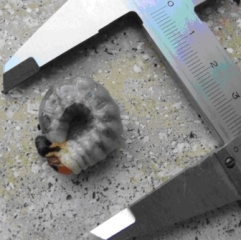

Third instar:

age - unknown

weight - 21.5 g

HCW - 11.95 mm

length - 8 cm

Photo by Bert van Geel.

|

In order to grow stag beetle larvae have to moult and they will do that twice as they have only three instars, shown above [6]. By the end of their first year they generally have reached their third and last instar. Then, depending on the weather, they will stay in that instar one year fattening up; longer if they underwent a cold winter and/or spring. In any case, mature larvae might be present when new eggs are laid in the same nest. Also, this explains why sometimes one can find together larvae at different stages of development. Click here for and example found by Heinz Rothacher.

If you want to know more about stag beetle larvae click here.

Return to the top

Pupation stage:

when they are fully grown the larvae stop eating and leave for the soil where they will take quite a bit of time to make a cocoon; probably at least 2 months. Inside it the larvae will moult for the third time and undergo metamorphosis into a pupa in a protected environment.

In the UK mature larvae probably start preparing their cocoons by the end of May/ beginning of June; further south it could occur later [1].

The cocoon is nice and smooth inside. It is held together by special larval secretions and lined with the gut contents, it provides essential shelter for the very vulnerable pupa.

Larva ready to pupate, it has changed shape and colour. Note that this happened in captivity in very dry conditions, so it was unable to make a proper cocoon. Photo by Maria Fremlin, 3 July 2008.

|

More changes have occurred in the same larva, it now looks a bit like a doll; pupa in Latin means a doll. Photo by Maria Fremlin, 14 July 2008.

|

The larva has now metamorphosed into a pupa and shed its skin which has split right down the back. Photo by Maria Fremlin, 15 July 2008. Unfortunately because it was not in a proper cocoon it was attacked from below by woodlice and died. See this video.

|

At this stage the larvae have gone through metamorphosis and now the pupae bear a very close resemblance with the adult beetles. Note below how easy they are to sex.

Male stag beetle pupa. Photo by Maria Fremlin, 19 July 2012.

A larva was collected in the wild and then placed in a glass box with soil with the right humidity where it pupated successfully. Note how well formed its cocoon is.

|

Female stag beetle pupa. Photo by Maria Fremlin, 16 July 2011.

|

And next to each other; the female is on the top. Photo by Maria Fremlin, 20 July 2011.

|

For more about this stage visit Stag beetle pupal stage.

Return to the top

Adult stage: the imago may stay inside the cocoon or not. In any case it will always remain under the ground for several months until it emerges at the end of the spring. It emerges around late May in the UK but probably a bit earlier further South [1], then it flies outside.

Male stag beetle, apparently still inside its cocoon, found in Richmond Park, London, on 26 January 2007 when a dead tree fell down. Its antlers were spotted in the soil that was still attached to the tree; it was probably 30 cm below the ground before it was disturbed. Photo by Mark Wagstaff.

|

Male stag beetle found inside its cocoon, late May. It was at 40 cm depth, near the rotten roots of an ash (Fraxinus spp.) tree where stag beetle larvae were also found feeding. Click on the picture for another view.

Photo courtesy of Heinz Rothacher.

|

Female stag beetle found inside its cocoon, early April, 2006. It was in the roots of an old oak (Quercus robur) stump, about 3 meters high. There was also 1 larva, 7 females, of which one was dead, and 14 males, of which 4 were dead.

Photo by John T. Smit.

|

Return to the top

Emergence:

Stag beetles will make their way up to the surface and emerge through holes like this one. They do it with the help of their mandibles and their front legs which are also very strong.

Photo by Maria Fremlin, late May.

|

This beetle was right underneath a fresh hole; it nearly bit an enquiring finger. For more about this nest click here.

Photo by Maria Fremlin, 16 May 2009.

|

Male stag beetle emerging between the slabs of the

pavement along a London road in the vicinity of Richmond Park.

This photo appeared in the Richmond Park Biodiversity Action Plan, page 96. Photo by Mark Wagstaff, 26 May 2005.

|

Return to the top

* http://www.insect.jp/document/rep05/rep05.htm - In this website a Japanese breeder managed to get 90 larvae from one female stag beetle, in Japanese.

References:

[1] Franciscolo, M.E. (1997)- Coleoptera, Lucanidae, Fauna d'Italia, 35: 228 pp. Edizioni Calderini, Bologna, ISBN 88-8219-017-X. [This book is now out of print but a pdf is available on request.]

[2] Kretshmer, K. (2007) - Untersuchungen zum Ausbreitungsverhalten des Hirschkäfers (Lucanus cervus) mittels Radio-Telemetrie Sachbericht. AZ: 51.2.6.02.25-3008/03; Biologische Station im Kreis Wesel. http://www.bskw.de

[3] Tanahashi, M., Kubota, K., Matsushita, N.& Togashi, K. (2010) - Discovery of mycangia and the associated xylose-fermenting yeasts in stag beetles (Coleoptera: Lucanidae). Naturwissenschaften 97: 311-317.

[4]

The larval stage duration of “at least 2 years” is based on Maria Fremlin's research

carried out in Colchester, UK, listed in the UK diagram page.

[5] The larval stage duration of “at least 3 years” is based on research carried out in Germany and the Netherlands, listed in the Continent diagram page.

[6] Fremlin, M. & Hendriks, P. (2014) Number of instars of Lucanus cervus (Coleoptera: Lucanidae) larvae. Entomologische Berichten 74 (3): 115-120. [PDF]

Links:

The reproductive system a female Lucanus cervus

Lesser stag beetle life cycle

Life cycle photos of Lucanus capreolus, a north American species.

Last modified: Wed Feb 10 2016

| Main | Stag beetles' life cycle | Stag beetle life cycle drawing | Top |